Local tradition in Mungku Baru has kept high-value ironwood trees from being felled over the years.

Today, however, some of the trees lie in a timber company’s concession.

The villagers’ beliefs have been codified into customary law.

Although it is administratively part of Palangkaraya in Central Kalimantan, the village of Mungku Baru is far from the city in both distance and development. Cell phone signal is scarce, and there is no government electricity. Several houses have small solar panels, while others rely on generators for power – but 40,000 rupiah worth of fuel only lasts until 9 p.m.

Two hundred families live in Mungku Baru. Most are farmers, many have rubber plantations, some scour the forest for honey and traditional medicines.

“We also grow dry-land rice,” Anton, one of the villagers, told Mongabay. “We plant in October and harvest in March. It’s all organic. We don’t use chemical fertilizers.”

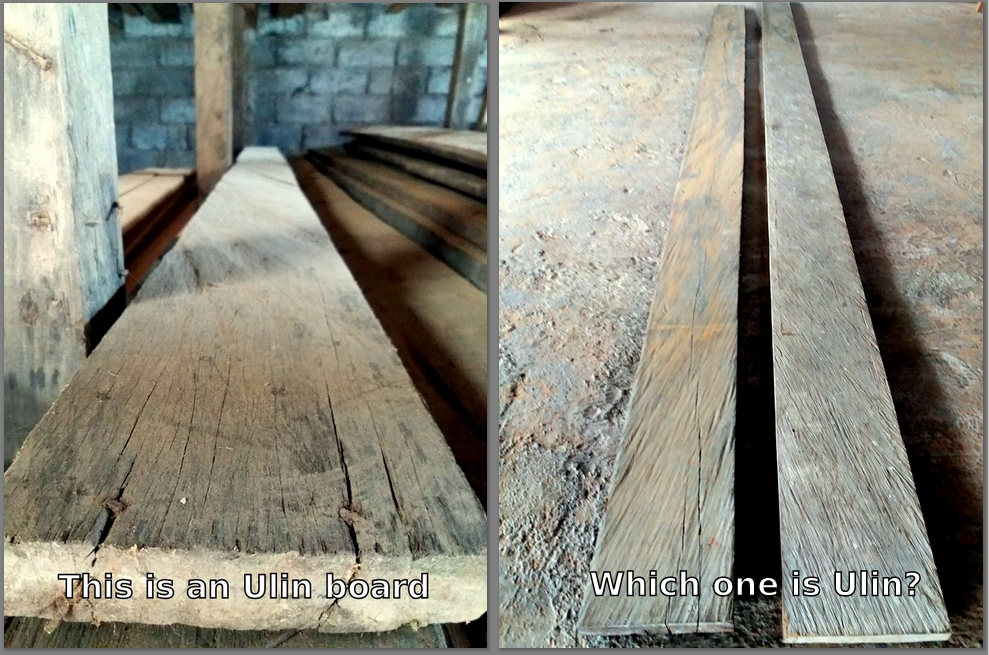

The most prized aspect of the village, however, is its rare ironwood forest. Known locally as ulin, Eusideroxylon zwageri is a high-value timber species and is often the first targeted by loggers. Its slow growth rate produces a tight grain that resists rot and termites. Ironwood buildings last for hundreds of years in the harsh wood-devouring climate of Indonesia.

The ironwood forest is located upriver of the village, besieged by PT Taiyoung Engreen, a timber company that is clear-cutting the surrounding forest. The company has, so far, respected the villagers’ rights to the land, leaving it untouched.

“The company has never disturbed our ironwood forest,” said Redie, one of the forest’s caretakers. “Therefore it is still in good condition.”

There are no roads or trails through the preserve, and unlike most rainforests still remaining in Kalimantan, there are still large-diameter trees and a wide diversity of other flora and fauna.

From this patch of land, the locals harvest several varieties of traditional medicine, such as iro, a fern used for treating liver ailments; tusuk kesong, a long tree root used for asthma; kelanis, a general purpose medicine; gensing, used for arthritis; belawan bark, good for diarrhea; semar, also used for asthma; and ants nests, for treating mumps. In addition, the locals believe the roots of the ironwood tree can be consumed to increase endurance.

“We don’t sell these medicines, but use them for our own needs,” Redie explained. “In the future, we might start a small business [in medicinals].”

A recent survey of the 500-hectare ironwood forest found 192 ulin trees greater than 20 centimeters in diameter. Despite a ban on export of new Kalimantan ironwood, vendors on the Chinese e-commerce site Alibaba still list Kalimantan ulin at upwards of $3,000 per cubic meter. At this price, rough calculations place the value of those trees at well over $360,000. Luckily with the recent redline on import/export it had became increasingly difficult to export new Ulin. Only reclaim Ulin from disused structure is officially authorized for export.

Even so, the locals are not interested in selling. They consider the forest sacred and rarely enter the preserve.

According to Hester Talajan, the traditional historian of the village, their ancestors saw that people were rapidly cutting the forest and worried there would soon be nothing left. To protect the forest, the ancestors called upon the spirits to guard it, stating that whoever dared to cut the trees would meet with untold disasters that would affect their family for generations.

This curse was then codified into customary law, a system of governance and penalties determined at the village level according to traditional rules. In the past, the fines for breaking the law were paid for with goods and crops, but now they consist of monetary penalties. One kati, or unit of punishment, costs 100,000 rupiah. If someone is found guilty of cutting a tree in the protected forest, the village elders and the forest guardians will determine how many kati the offense warrants.

The people of Mungku Baru formally established an ironwood forest governing body in September 2014. However, this group, and the village’s claim to the land, has yet to be officially recognized by the Indonesian government. This crucial step would provide long-term security and much needed funding to patrol the forest and protect it from outside threats.

“Our expectations are high,” said Aries Antoni, the village head. “We hope to protect and cultivate the forest. We wish to work together with other groups, but as of now we still have no legal claim to the land.”

This puts the village in a difficult position as competing interests continually threaten the ironwood forest’s fate. For example, although the timber company has respected the village’s wishes up until now, Aries fears they will change their mind once they finish harvesting the rest of their concession.

Further, another group has claimed that the ironwood forest rightfully belongs to them.

“It’s not true,” Aries said. “They staked their claim without any public discussion, and don’t care about the interests of Mungku Baru.”

However, without official government recognition of Mungku Baru’s claim, the fate of the forest remains uncertain.